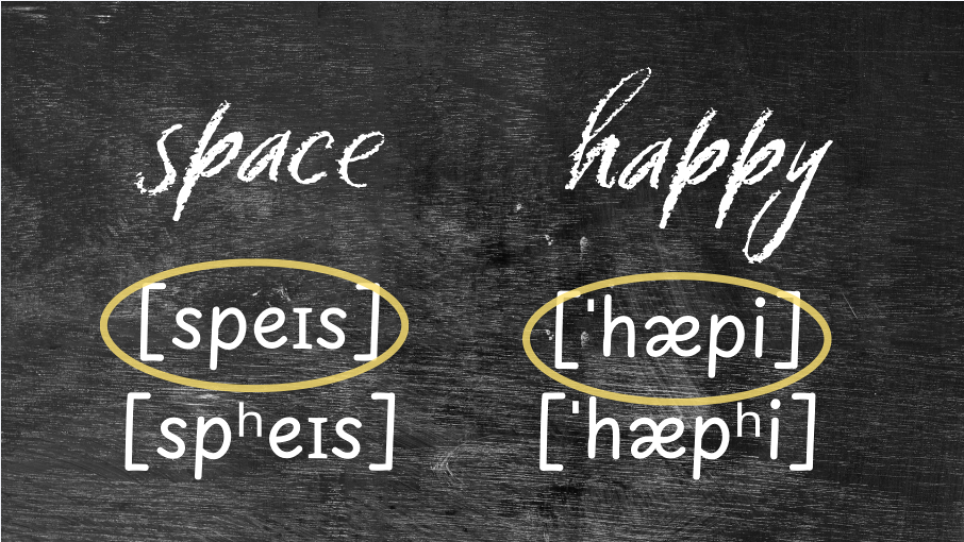

While learning a second language, various pronunciation rules often confuse learners. For example, the spelling of English words does not correspond exactly to their actual pronunciation and differs from the popular “natural pronunciation” method in the field. Take the letters “P”, “T”, and “K” as an example; if they are spelled immediately after an S, they are usually not aspirated. Therefore, the pronunciation of “SPACE” is similar to [speɪs][1] rather than [spʰeɪs]. When “P”, “T”, and ‘K’ appear in weak, unstressed syllables, they are also not pronounced as aspirated sounds. For example, American English pronounces “HAPPY” as [ˈhæpi] instead of [ˈhæpʰi].

[1] All phonetic transcriptions in the text are presented using IPA symbols to aid pronunciation and comprehension.

Accurate pronunciation relies heavily on listening

Professor Yu-An Lu of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (NYCU) observed that Chinese speakers often rely heavily on visual and orthographic memory when learning English vocabulary and pronunciation. In Taiwan Mandarin, the sounds “ㄆ” [pʰ], “ㄊ”[tʰ], and “ㄎ”[kʰ] are all aspirated. When Chinese pinyin conventions are directly transferred to English, learners of Taiwan Mandarin tend to pronounce English “P”, “T”, and “K” with aspiration as well. Professor Lu’s research team recently conducted a phonetic imitation experiment and found that Chinese-speaking participants could more accurately imitate the difference between aspirated and unaspirated sounds when they only listened to English pronunciations. However, when the participants were also shown the English spellings (e.g., on word cards), they often “could not hear” the difference and reverted to applying Chinese pinyin conventions, resulting in English spoken with a “Taiwanese accent”

Linguists refer to the awareness of pronunciation, spelling, and grammatical rules as “metalinguistic awareness”. People usually do not explicitly learn these features of their mother tongue, making it difficult to explain their language knowledge because this awareness is internalized. However, when learning a second language, metalinguistic awareness often interacts with that of the first language in complex ways. For example, this study shows that Chinese speakers learning English have their “hearing” influenced and limited by their visual and Chinese spelling habits, which affects their pronunciation performance.

“When people worldwide learn a second language, they are influenced by their first language and metalinguistic awareness, often incorporating features of their mother tongue. Therefore, ‘Taiwanese English’ is not a pronunciation error or problem, but rather a set of phenomena that arise when two language systems interact—something particularly interesting to us as linguists,” Prof. Lu explained. “For example, Chinese rhymes often end with a vowel and usually cannot add a consonant. When some Taiwanese children learn English, they tend to emphasize the final consonants, such as the “T” in “WHAT” or the “K” in “CAKE.” Rather than calling this mispronunciation, we should recognize it as a systematic reflection of their first language’s characteristics.”

No superior or inferior. All languages are equal.

“A second language cannot be learned as ‘naturally’ as the first language, and it is necessary to have guidance to understand the differences between the two.” Prof. Lu shared, reflecting on her own English learning experience in senior high school. She explained that without exposure to native speakers, a teacher’s metalinguistic knowledge could profoundly shape students’ awareness of English. For example, the difference between tense and lax vowels (e.g. “sheep” and “ship”) relates to tongue position and mouth shape, but her teacher described them only as long and short sounds, which was imprecise. “Therefore, I think every English teacher should study linguistics to help students systematically and precisely summarize the rules of learning a second language, so that students can open up the “conception and governor vessels” more quickly!” she said wittily.

During her bachelor’s studies in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, Prof. Lu encountered many students who spoke English with a fairly “standard” accent. To adjust her own English accent, she first listened carefully to the differences among various accents and then gradually imitated and learned from them. Her linguistic training also heightened her sensitivity to subtle language changes, which helped her learn and fine-tune her second language. However, Prof. Lu emphasizes that, as a linguist, language is language—there are no superior or inferior accents. Whether it is “Taiwanese English” or other accents, they all arise from different language systems. People may perceive an accent as “noble” or “vulgar,” or associate it with social status or education level, but these are meanings and value judgments imposed by the social structure of the time.

On the other hand, even within English-speaking countries, accents vary widely, and what is considered “vulgar” in one region may be regarded as “elegant” in another. Prof. Lu suggests that instead of trying seeking a single pronunciation standard, language learners should be exposed to a diverse range of accents, languages, and cultures: “Language accents are like a spectrum with many possibilities. If we only accept one accent as ‘correct’, we risk believing it is superior to others, and fail to understand accents and culture. Every language and accent is equal. When we set aside value judgments of good or bad, the more languages and accents we embrace, the more effective our communication becomes.”

Seeing the world anew through language

Building on her laboratory phonological research on second language acquisition, Prof. Lu has recently focused on the intergenerational tonal changes in Taiwanese Southern Min. She noted that while dialect tones historically took over a century to evolve, contemporary Taiwanese Southern Min dialects are undergoing radical tonal shifts within just one or two generations. This accelerated change marks a unique opportunity to study the languages spoken in Taiwan, especially as the number of speakers of various local languages is rapidly declining.

For example, Prof. Lu noted that regarding the checked tones of Taiwanese Southern Min, because Mandarin has no words with checked tone ending in “P,” “T,” or “K”, and the younger generation has limited exposure to Taiwanese Southern Min, they are acquiring the language more like a second language or “heritage language.” This shift is changing their perception and production of checked tones. Such cross-generational variation is occurring at an astonishing rate. At the same time, influenced by Taiwan’s multilingual environment, Taiwan Mandarin is developing its own characteristics, such as the merger of “厶”[s] and “ㄕ”[ʂ] and confusion between the syllable codas “ㄣ”[n] and “ㄥ”[ŋ].

Through laboratory phonological research methods, Prof. Lu has paved a research path to uncover the direction and patterns of different languages spoken in Taiwan. In fact, NYCU’s Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures encompasses a wide range of research areas. “For example, Professor Ho-Hsien Pan is studying how acoustic features can improve the understanding of autistic speakers. Professor Tsung-Lun Wan has long researched identity politics and language use among hearing-impaired individuals and other marginalized groups,” Prof. Lu added. From a sociolinguistic perspective, Singlish, which was once considered “substandard,” has now become a key symbol of Singaporean national identity. Similarly, “Taiwan Mandarin” or “Taiwanese English” today may also reflect a growing local consciousness. Clearly, linguistic research at NYCU not only introduces innovative scientific perspectives but also encourages the public to rethink the complex relationship between language, culture, and society.

NYCU Elite: https://elite.nycu.edu.tw/

NYCU: https://www.nycu.edu.tw/nycu/en/index

Interview |Fu-Kuo Chu

Translation | Yi-Chen Emily Li

Editing | Hsiu-Cheng Faina Chang / StoryLab

Photographer | Hao-Yun Peng and Yen-Yu Shih / ZDunemployed studio